This is an 18th century(-ish) protest song or poem on the enclosure of common and waste land, though the tune I’ve recorded is my own. There’s a relevant thread on Mudcat. There is also an article I found more recently on Mainly Norfolk that links to a nice video version by the Askew Sisters (their tune, not mine!) This article expands on a chapter in my book So Sound You Sleep. It’s also been posted to the Wheal Alice Music section.

There are a number of variations of this verse, which is usually assumed to date from the 1750s or ’60s, when enclosure legislation started to accelerate dramatically, though the appropriation of common land for private use goes back much further. There’s a two-verse variant that’s often seen on the internet as a meme, which consists of the first two verses (more or less) of the first variant below (which happens to be the one I put a tune to) and is said to date from 1764 or thereabouts. It’s often described as a nursery rhyme, and it’s often speculated that some nursery rhymes are may be a metaphor for a political or other significant social event. For example, Ring a Ring-o’ Roses is sometimes said to relate to the Black Death or the Great Plague, and Rock-a-bye Baby to the Glorious Revolution. In Goose and Common the political reference is much more straightforward, which is why I included it in an album of songs of political or social comment, but that doesn’t necessarily mean it was never recited or sung to or by children.

Here are two versions of the lyric, with quite a lot of background material following.

Goose And Common lyric

In my setting, I repeat the last line of each verse. That repeat is not in any of the texts I compiled it from, but I thought some close harmonies in the chorus might be nice. Well, close-ish.

They hang the man and flog the woman

Who steals the goose from off the common

Yet let the greater villain loose

That steals the common from the goose.

The law demands that we atone

When we take things we do not own

But leaves the lords and ladies fine

Who take things that are yours and mine.

The poor and wretched don't escape

If they conspire the law to break

This must be so but they endure

Those who conspire to make the law.

The law locks up the man or woman

Who steals the goose from off the common

And geese will still a common lack

Till they go and steal it back.

Another (later) version

They hang the man and flog the woman

Who steals the goose from off the common

Yet let the greater villain loose

That steals the common from the gooseThe law doth punish man or woman

That steals the goose from off the common

But lets the greater felon loose

That steals the common from the gooseThe law locks up the hapless felon

who steals the goose from off the common

but lets the greater felon loose

who steals the common from the gooseThe fault is great in man or woman

Who steals a goose from off a common

But what can plead that man's excuse

Who steals a common from a goose?

[In The Tickler Magazine 1 February 1821]

The Inclosure Acts

Privatization of public assets didn’t start with the Thatcher government, surprisingly enough.

The Inclosure [sic] Acts of the 18th and 19th centuries were the culmination of a long ongoing process by which common and waste land passed into private ownership over the course of several centuries. (Inclosure is an archaic spelling of enclosure.) The first Inclosure Act was passed in 1604, but the process had been ongoing less formally for centuries before that. Farming became more “efficient” and redundant workers were forced to migrate to urban areas, which had a pronounced impact on the growth of the Industrial Revolution.

Kingsland

Kingsland is one tiny example of the enclosure of private land, but it’s one I happen to know something about, since it’s the part of Shrewsbury where Thomas Anderson was executed, but it also exemplifies the issues raised in Goose and Common, having been acquired under Inclosure legislation.

My song about Thomas Anderson, based on an article by the late Ron Nurse, will be making an appearance here sooner or later. In brief, though, Anderson was executed by firing squad in the aftermath of the Jacobite Rebellion: the part of Kingsland where he died seems to have been close to where the Shoemakers’ Guild had its arbour, and to land later occupied by Shrewsbury Workhouse, and now part of Shrewsbury School. There’s something piquant about the thought of the sons of the privileged classes occupying the same (though somewhat altered) building that had previously been a Foundling Hospital and a House of Industry.

The entrance to the Shoemakers’ Arbour, all that remains of the original building and moved to the Dingle in 1875 or thereabouts.

Hulbert tells us in The History And Antiquities Of Shrewsbury:

KINGSLAND, is an extensive piece of ground on the opposite side of Severn from the Quarry . It belongs to the Corporation […] Upon what account it received the present name, it is not easy to say ; probably it was waste land belonging to the Crown, and granted to the Corporation , as it is in some old writings mentioned as uninclosed. The first accounts I have been able to get relative to this piece of ground are, that in the year 1529, at a Common Hall, the Common Pasture of Kingland was set for three years at £3 per year , and in 1586, ordered to be inclosed. The Annual Horse Races were formerly on this spot, it was then considerably larger, many enclosures having of late years been made on the out parts . In 1724, the whole of this land was let to Mr. Richard Morgan , of Shrewsbury , who sowed it with corn.

Common land originally belonged to the Lord of the Manor, but rights to pasture and other rights were held by other properties or tenants. Waste land was land not considered useful for farming, but was nevertheless often farmed by peasants with no other land. The various strips of common land were farmed by the lord and his tenants: serfs might be allowed to live on strips owned by the lord, but were required to cultivate his land.

As the common land became enclosed, former tenants often went to work in towns, providing the workforce for the large factories that appeared during the evolution of the Industrial Revolution.

Harley’s Stone

This is not quite as personal an artifact as its name might suggest. This tiny chunk of rock is known as Harley’s Stone, and can be found in the Quarry, Shrewsbury’s park across the river from Kingsland. In fact, it’s a stone’s throw (ahem) from the Dingle, where the Shoemakers’ Arbour now stands. Or what is left of it, i.e. just the gateway.

Like the Bellstone in the Morris Hall courtyard, in the town centre, Harley’s Stone is a glacial erratic: that is, a rock that isn’t of a type native to the area, having been deposited by a passing glacier.

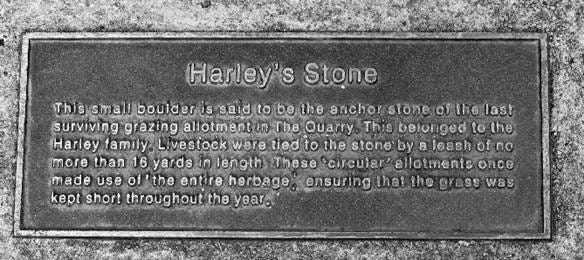

The plaque reads (in case you’re reading this on a cellphone-sized screen):

This small boulder is said to be the anchor stone of the last surviving grazing allotment in The Quarry. This belonged to the Harley family. Livestock were tied to the stone by a leash of no more than 16 yards in length. These ‘circular’ allotments once made use of ‘the entire herbage’, ensuring that the grass was kept short throughout the year.

My wife has suggested that we should demand ‘our’ bit of the Quarry back. However, I’ve no evidence of a direct link between my family and the Harley family of Rossall, Bicton, who apparently refused to sell their grazing allotment when the Corporation was acquiring land in the Quarry in the 18th century. I suppose we won’t be keeping a sheep there just yet. Especially as we no longer live in the area.

There is a genuine family connection apart from the name, though. My niece tells me that this is where her husband proposed to her. I’m sure he didn’t only want her for our claim to the property in the Quarry.

Kingsland and the Quarry effectively ceased to be common land by 1756, though the Corporation was still leasing some land for grazing, perhaps as late as the 1920s (Victoria County History Shropshire, Volume VI, part II).

Goosed by The Commons

Much more recently, enraged by a government devoted to selling off public assets, wholesale blocking of immigration, cronyism and the suppression of protest, I found myself writing a new version. While the privatization of common and/or waste land is more or less a done deal in the 21st century, the underlying topic of those who govern doing so for their own benefit, rather than that of the people, still has a very contemporary resonance. The lyric below makes that link more explicit: I don't know that the world needs it, but somehow it demanded to be written... I don't know that I'll perform it as a song, though, as I'm already performing the older version.

The point of the last line is that I was unimpressed at the sight of a very small group of Conservatives voting (again) for a new Prime Minister after the resignation of the one preceding – a small quirk of a deeply flawed electoral system. I wouldn’t be surprised if I found it necessary to revisit this piece to reflect events in 2025 better, though.

The law demands that we atone When we sell things we do not own Yet lets MPs and Lords so fine To sell off what is yours and mine The poor and stateless don't escape When they conspire the law to break This must be so, but we all endure Those who conspire to make the law You and I do not escape the web Of laws that profit from us, the plebs But MPs and their cronies too Use or ignore them as it suits The law forbids both man and woman To protest corruption in the Commons And so, we all will Justice lack Till we can vote to take it back...